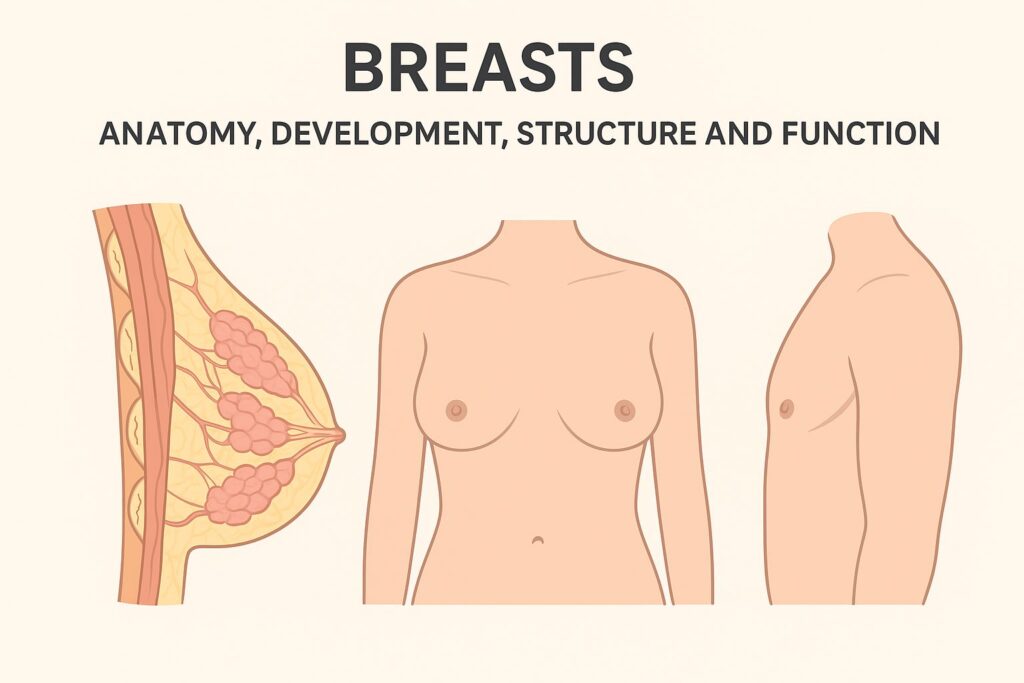

Breasts are an essential anatomical and functional part of the human body, present in both men and women. While male breasts remain undeveloped throughout life, female breasts undergo significant changes, particularly during puberty, pregnancy, and lactation. Understanding the structure and function of the breast is important for students of anatomy, medical science, and anyone interested in human biology.

What are breasts?

The breasts (mammary glands) are specialized organs located on the chest. They are composed of glandular tissue , fibrous tissue , and fatty tissue . Their primary biological function is to produce and secrete milk during lactation. Both men and women have breasts, but: In men, the breasts remain rudimentary. In women, they grow and develop during puberty and especially during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Also read this post :- Menopause and Osteoporosis: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment

Female breast anatomy

1. Location and size

In young women, the breasts are hemispherical structures located on the anterior thoracic wall . They extend

vertically from the second to the sixth ribs , and horizontally from the lateral border of the sternum to the mid-axillary line .

Axial tail

A superolateral extension called the axillary tail of Spence runs into the armpit region and is closely associated with the axillary lymph nodes .

2. Retromammary space

A loose areolar space behind the breast allows it to glide freely over chest muscles such as:

- Major pectoralis major

- serratus anterior

- external oblique

This space separates the breast from the deep fascia.

External features of the breast

1. Nipple

The nipple is a small, conical protuberance usually located in the fourth intercostal space . These include:

- 15–20 lactiferous duct openings

- Smooth muscle fibers that cause the nipple to twitch or contract

Retraction of the nipple during development can cause difficulty in breastfeeding.

2. Areola

The pigmented area around the nipple is called the areola

. Changes in color:

- Pink/light in virgins

- Darkening during pregnancy

- gets lighter after breastfeeding

The areolar glands enlarge during pregnancy and secrete an oily substance that protects the skin during breastfeeding.

internal structure of the breast

The breast is made up of three main components:

1. Glandular tissue

- It has 15-20 lobes.

- The lobes consist of smaller lobules

- Lobules contain alveoli (milk-secreting structures)

Each lobe drains into a lactiferous duct , which widens into a lactiferous sinus – a temporary milk reservoir.

2. Fibrous tissue

Connective tissue forms the Cooper ligaments , which support the breast.

In breast cancer, these ligaments can shrink, causing dimpling of the skin .

3. Fatty tissue

It surrounds the glandular tissue and largely determines the size and shape of the breast.

Breast development (mammogenesis)

Also read this post :- Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS): Symptoms, Causes, Treatment, and Prevention

Before puberty

- only ducts are present

- no alveoli

- Growth primarily due to fat accumulation

On youth

Estrogen stimulates:

- Branching of the ducts

- Formation of terminal buds

- Development of the initial alveoli

During pregnancy

Hormones involved: estrogen, progesterone, prolactin, growth hormone

The changes include:

- Formation of true milk-secreting alveoli

- Increased duct branching

- production of colostrum (yellowish, nutrient-rich fluid)

Lactation

It begins 4-5 days after the baby is born

. Stimulated by the baby’s suckling, the myoepithelial cells contract to push milk through the ducts.

After breastfeeding

- Milk stops

- alveoli shrink

- Glandular tissue decreases

After menopause

- Glandular tissue atrophy

- Breasts become smaller and thicker

Male breasts

Male breasts remain underdeveloped, including:

- Basic ducts (fewer in number)

- some fibrous tissue

- thick

These usually do not develop functional alveoli.

Blood supply, lymphatic drainage, and nerves

Blood supply

Where do breasts get blood from?

- Axillary artery branches

- internal thoracic artery

- intercostal arteries

Venous drainage

The veins form a network around the nipple called the venous circle , which drains into the:

- axillary vein

- internal thoracic vein

Nerve supply

From the 4th-6th thoracic nerves , providing:

- Sensory Supplies

- Sympathetic Fibers

Hormonal control, not nerves, is responsible for milk secretion.

Conclusion

Breasts are complex organs with significant structural, functional, and hormonal significance, particularly in women. From puberty to pregnancy and menopause, breast tissue undergoes significant hormonally controlled changes. Understanding the anatomy and physiology of the breasts is essential for medical students, healthcare professionals, and educational content creators.

Also read this post :- Lack of sexual desire in women

Frequently asked questions about breast anatomy, structure, and function

The breasts are composed of glandular tissue, fibrous connective tissue, and fatty tissue. The glandular portion produces milk, while the fatty portion determines size and shape.

The primary function of the female breast is to produce milk (lactation) to nourish the newborn baby. The breasts also play a role in hormonal regulation and reproductive physiology.

Male breasts remain underdeveloped and lack the alveoli that produce milk. Female breasts develop during puberty and can produce milk during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Lobules are small glandular units that produce milk.

Lactiferous ducts are the tubes that carry milk from the lobules to the nipple.

The nipple becomes erect due to contraction of the smooth muscle fibers within it. This can be caused by touch, changes in temperature, or hormonal stimulation.

The areola is the colored skin surrounding the nipple. It contains sebaceous glands that protect the skin , especially during breastfeeding.

During pregnancy: Alveoli develop, ducts enlarge, colostrum is produced, areolae darken, breasts increase in size, these changes prepare the breast for milk production.

Colostrum is the first form of milk produced during late pregnancy and the first few days after delivery. It is rich in antibodies and nutrients that protect the newborn baby.

Sagging breasts are caused by:

Loss of skin elasticity

Stretching of Cooper’s ligaments

Loss of glandular tissue after menopause

Nipple retraction can be congenital or caused by fibrosis. However, sudden retraction may be a sign of breast disease and should be evaluated by a doctor.

Where do the breasts get their blood from?

Axillary artery branches

Internal thoracic artery

Intercostal arteries

Breastfeeding usually continues for 5–6 months , although many women may breastfeed longer depending on their milk supply and the baby’s needs.

After menopause, glandular tissue shrinks and is largely replaced by fat, making the breasts smaller and softer.

No. Variations in milk production are due to:

Hormonal responses

Breast tissue development

Breastfeeding frequency

Overall health

Rarely, men may produce small amounts of milk due to hormonal imbalances, medication, or endocrine disorders, but this is not uncommon.